Why Inflation Is Not Caused by Corporate Greed

A nuanced look into the causes of inflation and if greedy companies are really the ones to blame

Since the 2021-2023 inflation surge, the causes of this recent inflation in Australia have bounced between mostly supply-side factors, mostly demand-side factors, or both. But a growing and popular (with laymen) hypothesis is that companies are exorbitantly increasing prices, opportunistically using recent inflation as an excuse to raise prices far more than cost increases to maximise profits. Not only that this is occurring, but that this is a significant cause of the inflation we are seeing today. This is wrong for many reasons, yet this idea is becoming more prevalent. This idea is being pushed by the mainstream media, some (very few) economists, the Greens party, and unfortunately even some Labor MPs (although to a much lesser extent).

I want to begin by providing an understanding of what causes inflation and how this period of inflation was caused, then I’ll go into the corporate greed narrative more and deconstruct the evidence they use to support it.

A Primer on Inflation and the Causes of the Recent Inflation

Inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. This increase reduces the purchasing power of money, with each unit of currency able to buy you less goods than previously. Inflation is not a bad thing, or at least a stable and low rate of inflation. Australia’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has an inflation target of 2-3% each year. In most periods in recent decades, we have been quite successful in remaining in this target. What has happened recently? Let’s first look at the three main and broad causes of inflation.

Demand-pull Inflation

The first cause is demand-pull inflation. This is simply when aggregate demand increases to exceed aggregate supply. Suppliers of goods and services can’t supply enough relative to the increase in demand, so they raise their prices which therefore also increases their profit margins. This also tends to raise wages as firms have an increased demand for labour, seeking to hire more workers. This may also cause higher prices of goods due to firms covering their higher labour costs. More jobs and higher wages increase household incomes and lead to a rise in consumer spending, further increasing aggregate demand and the scope for firms to increase their prices. When aggregate demand is below the economy’s potential output, such as under the lockdowns when the pandemic started, there is room (and a need) to increase aggregate demand and keep the economy from falling into depression. This is what both the Australian federal government did through fiscal policy and what the RBA did through monetary policy. Through deficit spending, the government committed hundreds of billions in stimulus to employers, employees and people on Centrelink. This helped to keep people spending and keep businesses afloat.

The RBA also stepped up at the same time to deliver monetary policy that would stimulate the economy. An initial step taken was lowering the cash rate. The cash rate is the market interest rate for overnight loans between financial institutions. Without going too in depth, the RBA changes the cash rate by adjusting the policy interest rate corridor. The RBA maintains the cash rate by using open market operations, which involves repurchase agreements, bond buying and selling, and foreign exchange swaps. With both repurchase agreements and bond buying/selling, when the RBA lends or buys a bond, it injects cash into the financial system, increasing the money supply. The cash rate has a strong influence on other interest rates such as deposit and lending rates for households and businesses. Lower interest rates increase aggregate demand by incentivising people to spend. This is because lower interest rates on bank deposits reduce the incentive to save money. Lower interest rates for loans can encourage people to borrow more, and lower lending rates can increase investment spending by businesses. If a household has a variable-rate mortgage for example, lower interest repayments allow the household to spend more money. The RBA further reduced economic uncertainty by committing to not increase the cash rate for a certain period of time (forward guidance). The cash rate was eventually lowered to 0.1%, and without being able to lower it anymore; they needed other ways to lower interest rates. The RBA ramped up their asset purchasing, buying a large amount of assets (primarily government bonds), increasing the money supply and ensuring interest rates stay low, specifically also lowering long-term interest rates. This is known as quantitative easing. This also injects liquidity into banks to loan easier and provides liquidity to investors to purchase other assets. A couple other measures were used, but these were the main ones in their pursuit of expansionary monetary policy.

To return to demand-pull inflation, if the actions of monetary and fiscal policy increase aggregate demand so much that it exceeds the economy’s potential output; we would see demand-pull inflation. More on this shortly.

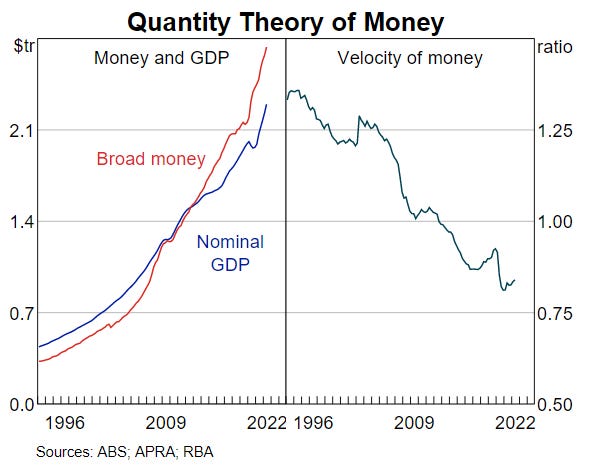

Before I move on, I want to quickly address the monetarists who believe money supply growth is the main cause of inflation through the quantity theory of money. The money supply increasing is important to inflation and excessive money supply growth is included under demand-pull inflation. The money supply did increase, dramatically. But the velocity of money - the rate at which money is exchanged from one entity to another - has significantly decreased over the past few decades. The below graph indicates that the velocity of money is not stable, contrary to what monetarists would believe.

Money supply just isn’t the whole picture as many used to believe. One can also look at Japan, they have been having problems with very low inflation and even deflation. They were even the first country to enact quantitative easing to spur inflation. They have therefore seen large money supply growth in the last few years, but without commensurate inflation.

Cost-push Inflation

The second cause is cost-push inflation. This occurs when aggregate supply falls, normally due to an increase in the cost of production. If aggregate demand stays the same, prices increase due to not being able to supply to the existing level of demand.

This can arise from an increase in inputs such as oil, or from supply disruptions in general such as natural disasters. The events since the pandemic started illustrate well all the many supply issues. Relating to COVID-19 specifically, there was of course initial supply chain disruptions with lockdowns stopping workers from working, and of course people not being able to work from being sick. This significantly continued even after the lockdowns, with many people getting COVID-19 and isolating, not being able to work. This continually got worse as the variants became more transmissible, and even with the vaccines there was significantly reduced access to COVID-19 vaccines in developing countries contributing to the global supply chain crisis. With supply constrained, and with an increase in demand particularly after the lockdowns, there was some heavy upward pressure on prices. This was heavily seen in the global chip shortage, as well as the bottlenecks in shipping port blockages from being overwhelmed with container ships and their cargo.

To further exacerbate all this… the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine began. The effects from this war have significantly affected supply of food, energy and mineral resources. With food, trade with Russia and Ukraine account for more than 25% of world wheat trade, more than 60% of global sunflower oil and 30% of world barley exports. This has been a big contributor to the increase in food prices and food shortages seen globally. With energy, Russia is the second-largest natural gas producer and the third-largest oil producer in the world. This has caused a global energy crisis, with the prices of natural gas and oil skyrocketing. High oil prices in particular is a very big deal, as oil is a major input in many sectors of the economy. High oil prices will lead to higher petrol prices, this makes the transportation of goods more expensive, making many goods more expensive. For minerals, Russia is a significant source of 35 critical minerals including 30% of the global platinum supply (including palladium), 13% of titanium, and 11% of nickel. The lack of mineral resource inputs also raises the price of goods.

On top of all the aforementioned, there has also been some domestic supply issues. The floods during 2022 caused many food shortages. Floods caused the complete destruction of soy and rice crops and 36% of macadamia nut production. It also caused massive loss of livestock and severe damage to farming infrastructure. This all led to shortages of fresh food, and high increases in the price of food. Besides the floods too, other poor weather has caused food shortages. Cold temperatures and catastrophic rainfall wiped out tons of crops, leading to shortages and therefore high prices for lettuce, cauliflower and zucchini among other vegetables. As well as the ongoing potato shortage, caused by high energy prices in European countries, low yield of potato crops due to rainfall in New Zealand and Australian crops being lost to floods.

The severe global and domestic supply issues have really created the perfect storm for inflation, with cost-push inflation being a massive contributor.

Inflation Expectations

The third cause are inflation expectations. They are the beliefs that households and firms have about future price increases. While demand-pull and cost-push inflation are crucial, the expectations of individuals in aggregate are more important than people think with regard to inflation. This is because peoples’ actions can contribute to a higher rate of inflation so that expectations about inflation become self-fulfilling. This can work in multiple ways. For example, if workers expect future inflation to be higher, they may demand higher wages now to make up for the loss of future purchasing power. Or if firms expect future inflation to be higher, they may raise prices of their goods and services at a faster rate.

What the RBA can do is try and anchor inflation expectations. By engaging in contractionary monetary policy and committing to return to the 2-3% inflation target, households and firms can expect that inflation will return to normal and they won’t change their behaviour to cause more inflation. Inflation expectations being anchored is extremely important. This leads me to find comments like these recommending the RBA to stop raising rates dangerous. If the Greens gained control of the RBA (extremely unlikely), inflation expectations would likely be unanchored, and more inflation would follow.

Summing up the Causes of the Current Inflation

The inflation we’re seeing today is majority caused by supply-side factors, but also significantly demand-side factors. The supply-side factors largely reflect persistent global supply chain disruptions, notably from the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. It also reflects on domestic supply disruptions caused by climate change induced weather events such as floods and heatwaves. For the demand-side factors, domestic and global demand have been strong since the economic recovery of the pandemic. This is due to a likely overshoot of both expansionary fiscal policy and monetary policy, as well as the faster-than-expected development of vaccines.

Supply chain disruptions elevating cost pressures cause companies to raise prices. These cost pressures are significant increases in resource cost growth and nominal wage growth. Note that I’m not saying wage growth is a negative thing or pushing the wage-price spiral narrative (more on that shortly), it is a positive thing; especially since real wages have been cut due to inflation. But it is undeniably a factor in increased operating costs.

I think proponents of the corporate greed narrative agree with this, but they point to the significantly increased profits that coincide with increased inflation as evidence of causality.

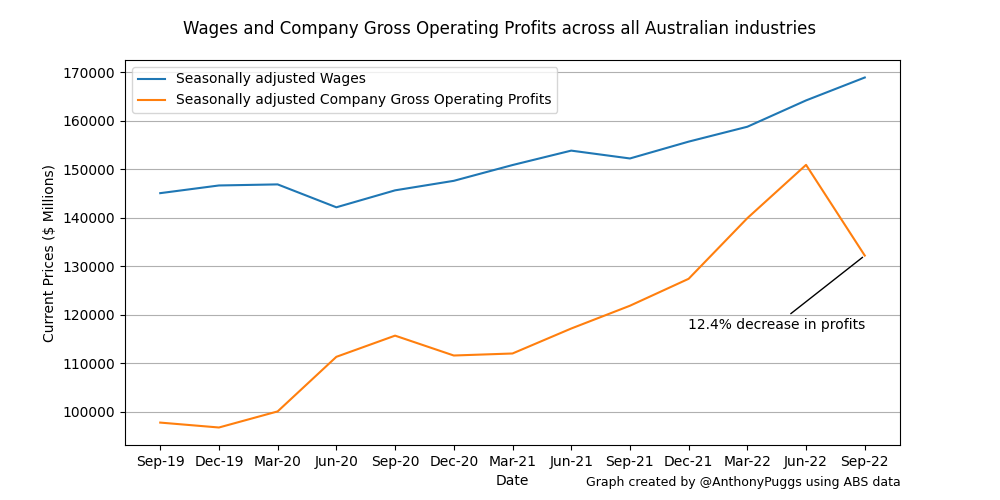

As you can see from the above chart, nominal wage growth is increasing, and company gross operating profits (CGOS) has significantly increased. This increase in CGOS is also when inflation started to surge (Q2 2021). Profits in Q3 2022 significantly fell by 12.4% compared to the last quarter. Can we simply point to the chart and see a decline in inflation then? Nope. Q3 2022 consumer price index (CPI) rose 1.8% MoM, the same as Q2 before the decrease in profits, and Q4 2022 rose 1.9% MoM. This is why it is not as simple as some may have you believe.

Inflation, Profit and Wages

Let’s address the inflation and profit relationship a bit more closely here. People claim if prices are rising to cover the increase in operating costs, then profits should not increase. So why have profits increased so much? One reason is demand-pull inflation, as mentioned earlier it increases profit margins whereas cost-pull inflation tends to not. As illustrated below.

Another reason is that wage growth is lagging behind inflation. If wage growth followed more directly, profit margins would be less as the company would need to pay their workers more. Wage growth at 3.1% is being triumphed by 7.8% inflation. The reason why wages haven’t kept up is relatively simple although multifaceted. Wages are known to be sticky; this means that they are resistant to adjusting quickly to labour market conditions. This works both ways. When market conditions are poor, companies won’t cut their workers’ wages but instead just fire them, as getting your wages cut is quite demoralising and will likely affect productivity. Wages are better at following inflation, but it takes time. A factor that affects this is the power of trade unions, as they can use collective bargaining to get wage increases faster than normal negotiation. Trade union membership has declined significantly over the years, with only 12.5% of Australian workers being trade union members. However, trade unions are not required for significant wage growth. Particularly due to the currently extremely tight labour market of 3.5% unemployment, workers have the upper hand in being able to demand higher wages and other benefits while companies are competing to hire. There is significant wage growth, workers are negotiating, but one theory is that perhaps workers are negotiating for things other than wages such as remote work, flexibility and other perks.

While wages will continue growing, we generally don’t want wages to be in lockstep with inflation. If wages were say automatically indexed to inflation, that would significantly increase the likelihood of a wage-price spiral. As cost of labour is a significant cost to businesses, wage increases cause price increases which in turn causes wage increases, repeating in a loop. I want to be clear that this is not happening now, and I don’t believe the current situation is anywhere close to a wage-price spiral.

One other reason for the large profits is particularly the Big Oil companies. The war in Ukraine placed these companies in an advantageous situation to benefit from a favourable market due to high oil prices. The point of this post is analysing the relationship between profit and inflation. However, I do support a tax on windfall profits – or more generally, economic rents from fossil fuel extraction, as supported by the IMF. We had a similar tax in place for a very brief period, called the Minerals Resource Rent Tax – an amazing tax unfortunately repealed by the Coalition under Abbott.

I think we can all agree that companies are ‘greedy’. Or to use a much better term, they are profit maximising; this is generally a positive thing (absent market failures of course). Companies suddenly becoming greedier makes no sense, did companies become more generous during periods of deflation? A better, but still largely incorrect view is that dominant corporations in uncompetitive markets take advantage of their market power to amplify inflationary impacts of both supply and demand shocks.

Market Power and Supply Shocks

However, there is some interesting research looking at how market concentration and market power can amplify price effects of supply shocks. A paper from the Boston Fed found that an increase in market concentration is associated with a 25% increase in the pass-through of cost shocks emanating from supply shortages, energy price shocks, and labour market shortages. The increase in market concentration is pivotal here, as they note that an increase in US market concentration was found as the COVID-19 pandemic started. I could not find data on Australian market concentration post-pandemic, although it has been increasing for decades. There are a couple things I want to look at, particularly the methodology. I will try my best to keep the econometrics brief! Central to the paper, they regress producer price increases on an index of concentration, the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). This is generally frowned upon. The reason why is because the relationship between price and HHI is not casual as both are equilibrium outcomes determined by demand, supply, and the factors that drive them. The authors note this and use the ‘granular instrumental variables’ method to solve the problem of endogeneity and attempt to establish causality. But a recent paper authored by over 25 economists specialising in Industrial Organisation (IO) talk extensively about their doubts in establishing causality and how it goes deeper than just an endogeneity problem. They claim that even if there was a causal effect of the HHI on price, it would be very difficult if not impossible to find instrumental variables (IV) that satisfy the conditions necessary for their use. They also claim that even if one finds such IVs, (like the granular IVs in the Boston Fed paper) they cannot find a causal effect that does not exist. Instead, likely obtaining a complicated mixture of supply and demand effects. So, for this I am placing my trust in the IO economists and remaining sceptical.

Another thing to note is that the firms used in the HHI are only publicly traded firms. Why would they only use data on public firms? Apparently, it’s because the data is easily available through Compustat, a newly popular data source in macroeconomics. Now if public firms look very similar to the rest of the economy, it could still give a consistent measure of concentration, and all is well and good. Unfortunately, this is not the case. For this, I look to a recent paper that shows how using Compustat to calculate concentration through the HHI is highly problematic. They find a very low correlation between Compustat (all public firms) data and U.S. Census data (all public and private firms) for concentration. The difference is so large that some results from studies utilising Compustat measures break down when using Census measures instead.

Given the methodological uncertainty, I am hesitant to accept this paper as proper evidence of corporate greed causing inflation.

Market Power and Demand Shocks

Another paper provides a convincing theoretical explanation of how market power can amplify the inflationary impact of demand shocks. The authors use the concept of the strategic industry supply curve which they developed in an earlier paper. They claim macroeconomists are missing certain microeconomic foundations like their model in the analysis of the interaction between inflation and market power. The strategic industry supply curve is used to generalise the standard Marshallian supply-demand analysis of competitive markets to the general case of imperfect competition. Using this, they show that inflationary demand shocks may generate price variation as a result of profit-maximising behaviour by firms with market power, varying in intensity per the competitiveness of the market.

While an interesting paper, the authors themselves deny this supports the corporate greed narrative. In an article written about the paper, they say ‘although our analysis does not support the simplistic view that inflation is being driven by market power, it illuminates the way in which market power and inflation interact.’

It is also worth noting what economists in general think about the relationship between market power and inflation. They were asked about the statement, ‘A significant factor behind today’s higher US inflation is dominant corporations in uncompetitive markets taking advantage of their market power to raise prices in order to increase their profit margins’. 67% of economists disagreed with this with only 7% agreeing, and the rest unsure.

Australian Analysis

I want to look more into the Australian analysis of corporate greed and inflation, but the analysis is not nearly as thorough as the Boston Fed paper for example. In Australia these articles promoting the corporate greed narrative always cite the Australia Institute with some very shoddy analysis. One recent article claimed that corporate greed has caused 70% of the inflation, which is an unreal claim; one that would make most economists howl with laughter. I can’t go over everything they have done but I will look at one ABC article and the ‘evidence’ they used.

Essentially, this article goes over the same narrative I have spoken about so far. It’s not entirely rubbish by the way; they go over demand-pull and cost-push inflation and how the supply shocks have contributed to inflation. Where this article takes a nosedive is where they say ‘But there’s now evidence companies are raising their prices over and above the increase in those costs’. Let’s have a look at the evidence. They use the NAB 2022 Q4 small and medium-sized enterprises business survey which looks at over 700 firms to analyse business conditions. They say the evidence from this survey suggests fatter corporate profits are contributing to inflation. Looking at the numbers comparing Q3 to Q4:

· Purchase cost growth dropped from 2.4% to 2.1%

· Labour cost growth dropped from 1.9% to 1.5%

· Final price growth dropped from 1.7% to 1.5%

While the growth numbers are all elevated, there is a significant decrease in all of them, there is no evidence of what they’re claiming. If they think (I’m guessing here, they don’t say this explicitly) the final price growth should have decreased more given input cost growth, it just isn’t that simple.

Let’s compare Q2 to Q3:

· Purchase cost growth remained at 2.4%

· Labour cost growth rose from 1.4% to 1.9%

· Final price growth rose from 1.6% to 1.7%

If the first numbers are evidence for firms rising prices way more than costs, can we take this as evidence of firms not rising prices as much as they could in line with labour cost growth? Of course not. This is quite blatantly not enough information for the claim being made and certainly not evidence.

Why Blaming Companies Gets Us Nowhere

The policy implications that come out of blaming companies are ineffective and misguided. Some suggest price controls to limit companies raising prices and therefore decrease inflation. Without needing to go through the theory as to why this is bad idea, one just needs to look at the shortages and fuel lines from the 70s price controls in response to stagflation. When asked the question ‘Price controls as deployed in the 1970s could successfully reduce US inflation over the next 12 months’, 58% of economists disagreed, and 23% agreed. And of the 23% agreeing, all but one economist agreed price controls would reduce inflation but with severe consequences and therefore not being worth it.

The more appropriate policy implications are using anti-trust legislation to break up companies and increase competition. While this is good policy in industries that are abusing monopoly power, this as a solution to inflation just makes little practical sense.

In reality, the real solutions to inflation are being done. On the supply-side, bottlenecks in global supply chains are easing up, global shipping costs are decreasing and energy costs are decreasing. On the demand-side, the RBA have been pursuing contractionary monetary policy such as raising interest rates and quantitative tightening.

Conclusion

The causes of the global inflation I believe have been well established. With the evidence currently available, at most I could agree that some firms with market power can amplify the inflationary impact of supply and demand shocks. Claiming that this is a significant factor in inflation, or more broadly - blaming corporate greed has no basis in evidence. This sort of populist rhetoric is harmful and misleading to the general public, fuelling anger and resentment when the appropriate measures to address inflation are already being undertaken.

I wish to leave you with a final image, illustrating the relationship between greed and inflation.

If you would like to see the code and data used for the graphs I made, check out my GitHub!